THE IMPORTANT CONTINUITY OF A WINE VILLAGE

OCTOBER/DECEMBER 2021

CORNAS AND ITS RHYTHMS, INTACT DESPITE 50 YEARS OF CHANGE

When I first visited Cornas, the village that abuts the granite flanks of the Ardèche hills in the Northern Rhône, it bore its own tapestry of everyday agricultural life, the rhythms determined by the seasons: fruit trees, vegetables, vines, a few goats up on high, an acceptance that life was a cycle of working the land and handing it on to the next generation, hoping that their lot would gradually improve.

In those early 1970s, Valence, the large town across the Rhône, had an occasional bearing on Cornas, not so much as a draw for office labour, more as a threat to the Cornasien hillsides, eyed by la gente rica valencienne as potential land for building their glitzy villas.

I was involved in a campaign to halt such building, the international support group to Auguste Clape and his friends who led the charge in opposing such desecration. One or two houses had got through the net before the shutters came down - for a while. Take a look from the vineyard of Patou towards Saint-Péray these days, and carbuncles do sadly exist on former vineyard slopes.

50 years later, the rhythms of Cornas have changed on the surface, with commuting to Valence from new build zones all around the village. Nowadays, it is the growers who have to fit in with the previously external forces, such as furiously driven cars hooting at tractors around the rush hour, and other signs of urban impatience – the antithesis of a viticultural setting.

And yet, scratch below the exterior, and there is still the pulse of a wine community, manifested by little rituals that evoke the times of yore. One such example is the dwelling of Mickaël Bourg, whose path into being a vigneron resembles that of the once outsider Thiérry Allemand when he made his way in the early 1980s, Thiérry starting with 0.16 hectare of 1961 Syrah, and another 0.1 hectare of overgrown land beside it – scraps, good scraps even, but scraps nonetheless.

Mickaël had no connection to the land – his grandfather was a mason at Cornas - and worked for two years as a mechanic before his first steps into the life of a vigneron in 2004, when he was 27. He started by working for Matthieu Barret of Domaine du Coulet, whose family owned around 10 hectares, and whose father had served as Mayor of Cornas – very much the top table.

His first vines were rented from Matthieu, and gradually he increased his holding, creeping up to one hectare, then bit by bit up to two hectares: the image of a patch here and a patch there gradually accumulating would be an accurate one. Two plots of Saint-Péray – 0.26 hectare and 0.36 hectare – and a smidgin of 0.2 hectare on the plain of Cornas for a vin de pays complete Mickaël’s empire.

In 2021, Mickaël took a firm step forward, moving into the house of the late legend Noël Verset, and also working from his cellars, which he has tidied up himself. Mickaël fully acknowledges his little part in extending the history of Cornas viticole, regarding it as great good fortune to be where he is now, the mystique of Verset acting as a spur for him.

Noël’s legacy endures in other ways as well, one of them less obvious, for Thiérry Allemand sleeps in the maestro’s old bed – “it was far too good and antique to be thrown away”.

Hence there is still a continuity, a viticultural theme, simmering below the surface of Cornas, and long may that continue.

A VISIT WITH A DIFFERENCE

AUGUST/SEPTEMBER 2021

THE ZANY WORLD OF BERNARD FAURIE & HIS BUREAUCRATIC NEIGHBOURS

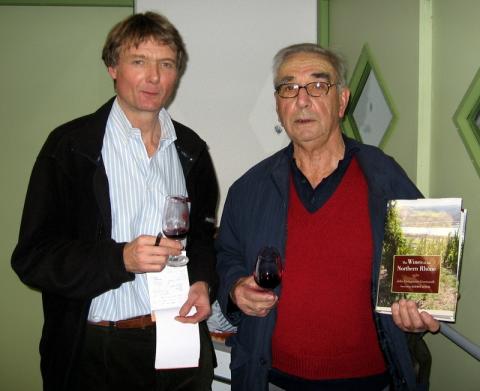

I have been visiting Bernard Faurie, the artisan grower of the Hermitage hill, since he left his factory job to cultivate the collection of family vines in 1980. We go way back.

From 2021, Bernard has relinquished most of his vineyard to his son-in-law Emmanuel Darnaud, retaining just a tidy 0.2 hectare on the wonderful Le Méal, vines planted by his father in the 1960s. These he will continue to work.

Emmanuel will be renting the other vineyards, 1.5 hectares in all, and needs to learn to make wine with the same lightness of touch as Bernard, not a given in an era when machines and muscle have often upstaged the thoughtful, hands-off approach.

On this occasion, probably somewhere near my 40th visit to Bernard, I found the great man in top form, scampering around even more than usual, and energized by the new reality of having more time to himself.

Now, a warning: if you see a seventy-something white haired individual wearing dark glasses whizzing towards you, be it in the streets of Tournon, or, more probably, in the hills above Tournon, it will be Bernard atop his electric scooter, taking absolutely no prisoners as he wheels along at great speed. The French for the scooter, trottinette électrique, is much more lyrical than the Anglo-Saxon, by the way, conveys images of high kicking Lippizaner horses stepping out.

“It goes very fast and well,” he comments; “I had a bit of a problem with 5 cm of snow up at 1,300 metres – the scooter got through it well at first, but then the battery shut down,” he says with marked disappointment, even bafflement. And the dark glasses? “I started wearing dark glasses to avoid being recognized.”

On this visit, I tasted both 2019 in bottle and the new 2020 vintage; after the whites, there were half a dozen of his deeply coloured reds. 2019 is a vintage of which Bernard says “I like it well – there’s a balance between tannins, power, finesse and elegance – and the wines travel straight, which they have to in my view.”

Having finished the tasting, I informed Bernard that I had a rendezvous fixed 100 yards across the road from his cellars for my Covid PCR test, very kindly fixed up for me by Coralie Jasmin when I visited her family in Ampuis, thank goodness for that. Bernard is a refusenik on the vaccine, so could give me no advice on the procedure I could expect.

My obvious newly acquired problem was the state of my teeth and my tongue, blackened by the tasting of the bold reds of Hermitage. Bernard kindly provided me with a bottle of Evian which I proceeded to gurgle and gargle under his pine trees in the garden. The pine trees are splendid, and, testament to Bernard’s green fingers, started life as his Christmas trees!

I then set off for the Laboratory Testing Centre, only to be met by a wall of typical latent French hostility as I announced myself to the receptionist – I could almost read the “Foreigner Alert – this man presents a problem” sculpted on her brow, backed by the aggressively delivered “you do realise that you have to pay for this?”

With much sighing and intake of breath from her, we commenced on the form filling. When we reached the contact email address on the form, I told her, in French, my address was jll . . . @ . . . drinkrhone.com. The fingers tapping the keyboard paused abruptly after the @ . . . She looked up and repeated, as a question “drinkrhone.com?”

I answered “oui . . . et j’espère . . . que . . . vous . . . drinkrhone…”.

Wham! Light switch moment. She was transformed. Off we went, swapping comments, humour included. Surely they could not refuse me my test now, I thought. Then came the dénouement - in France, they only check your nose, so all my frantic Evian efforts were rendered surplus to requirements, while the cost - €50 - was at least half that of GB. You do truly live and learn.

BONNE DÉGUSTATION to all.

2021: ADIÓS ROLLER SKATES

JULY 2021

NORTHERN RHÔNE 2021

THE SPELL HAS BEEN WELL AND TRULY BROKEN

The run of vintages on roller skates, when ripeness comes along smoothly, crop quality is high, and yields are pretty decent, is over for the Northern Rhône. 2021 is reverting to pre-solar days, marked by constantly changing weather veering between sudden heat, sudden collapses in the heat and a proliferation of rain, some of it very heavy.

This is on top of the frost destruction on 8 April. The damage was set up by a very hot March – people eating outside in temperatures of 25°-28°C. “The vines also thought it was spring, and off they went,” recounted YANN CHAVE at CROZES-HERMITAGE.

At CÔTE-RÔTIE, CHRISTOPHE BONNEFOND told me that his high vineyards on La Brosse lost 95% since they stayed in the shadow all that morning, whereas low zones in the same lieu-dit fared OK, high zones not – Mollard lost 90% at the top, nothing at the bottom. “On La Landonne, I decided to prune late and work against excess ripeness, so pruned in April, which meant the buds hadn’t broken.”

Frost hit vines have clambered back into some sort of contention, but it can mean that the same plant can have bunches ripening three to four weeks apart, with a lot of cutting and sorting needed come harvest time, a labour cost that will be high.

BLACK ROT ON SYRAH AT CROZES-HERMITAGE, JULY 2021

The late June, early July weather has brought the creeping menace of blight, with mildew and a relative outrider, black rot, on the agenda, the latter not seen since the run of hot years from 2009 started. Mildew is treated with copper, black rot with copper and sulphur treatments, but the latter’s treatments are only 60% to 70% efficient, I am told.

Growers report that this year they have already gone past the total number of treatments for the whole of the 2020 growing season. Hail arriving unusually from the East also hit Mercurol within the Crozes appellation in late June, 30% losses there in some vineyards, very localised.

It’s not all doom and gloom, though. STÉPHANE ROUSSET from the northern sector of hillside, terraced vineyards at CROZES-HERMITAGE told me: “yes, the rain means more work, but we have accumulated hot and dry years, and it’s good to return to less extreme temperatures, especially as the winter was very dry. For me, the rain is welcome.”

BERNARD FAURIE at HERMITAGE agreed: “the rain hasn’t been negative, since it was so dry in the spring: we still need to catch up on reserves. I don’t watch the quantity of rain – I watch how the soils conduct themselves – when they show a surfeit, that they are gorged, then there is a problem, not before.”

THIÉRRY ALLEMAND at CORNAS is also sanguine: “c’est bien,” he told me. “There’s been a bit of loss from frost and hail, but it’s an advantage that the vines are now growing well, flourishing, with large grapes forming. There won’t be a lot of harvest, but it can be balanced.”

It’s unlikely that the harvest date will fall before mid-September, a good two+ weeks later than the sometimes record early harvest dates of 2020. The prospect of a second consecutive vintage that can express terroir more than extreme weather influences is encouraging for all amateurs of Northern Rhône en finesse.

ONCE YOU MOVE FROM VILLAGES TO CRU, CAN YOU RAISE YOUR GAME?

APRIL/JUNE 2021

GO, RACHAEL BLACKMORE! GO RASTEAU!

RACHAEL BLACKMORE has been a jockey I have followed in Ireland for the past two to three years. She is extremely capable, and, had it not been for another rider’s attachment to the most powerful stable, she would have been Champion Jockey of Ireland by now. As it is that gent is now injured, and RACHAEL has just won the Grand National for her classy trainer HENRY DE BROMHEAD, the horse MINELLA TIMES, one that did not go unbacked in the L-L household, running off a very handy low weight.

Rachael recently hit the headlines over here through her inspired riding at the Cheltenham National Hunt Festival, where she rode six winners over the four days (27 races open to her, but not a ride in each of those), showing immense tactical prowess and determination, mixed with bouncing back from falls, on one day three of those. Now the NATIONAL is deep icing on her cake - history has been made.

Her story has been written up, and here is part of it from the Racing Post of Sunday 28 March, 2021. A young trainer called Denise O’Shea had linked up with Rachael at Christmas 2015, when Rachael hadn’t even ridden three winners; “I didn’t know Rachael before she rode for me,” recalls Denise O’Shea; “my regular jockey was at another meeting, and Rachael’s agent rang me, suggesting her. I said we would go with her. About an hour later this new number came up on my phone. It was Rachael. She wanted to come down and sit on the horse. Maybe that’s the sort of thing that happens in bigger stables, but it’s not the sort of thing that happens to a small outfit like mine.

By turning professional, she knew she’d have to work ten times harder to get where she wanted to be. She always had the talent, but you have to put in the work and she did that.”

From my point of view, Rachael, who at 31 is at the top of her game, allies tactical sense – where to have her horse on the track, with a view to besting other jockeys if in a tight pocket around a bend, for example - with very good judgment of pace, the latter allowing her horses to run efficiently over any distance from a fast 2 miles to a steadier 4.5 miles, as she did with Minella Times.

Rachael’s story brought to mind what happens when a VILLAGES appellation is promoted to the ranks of full Cru, similar to Rachael’s turning professional. There is work to do to justify the extra status, improvement has to be forthcoming. In the SOUTHERN RHÔNE, the most recent example of rising to Cru has been CAIRANNE, preceded by RASTEAU.

RASTEAU recently celebrated the first 10 years as Cru. Upon their promotion, I told ROBERT CHARAVIN, the lanky, forthright, kick-ass PRESIDENT of the GROWERS UNION, the SYNDICAT DES VIGNERONS, that they had three years to make their mark. My message was that at all costs, growers had to be driven away from thinking that Cru equalled licence to raise prices and sit back and watch the money pour in.

The key in such circumstances is Quality and Communication. Growers have to push to be more mindful of their vineyards, and to be more detailed in the cellar. Perhaps investment is required to make marginal gains – that could be equipment, better crop sorting, higher quality corks, a myriad of steps along the path from vineyard to bottle. It can mean hard work, just as it did for Rachael.

Communication is also important. The world needs to be aware that this is a vineyard to be reckoned with. There can be fun communiqués, convivial events – at RASTEAU, the middle of May in normal times is when there is a joyful walk for hundreds through the vineyards, a trek of some kilometres with the scenic accompaniment of the garrigue, the pine trees, the green oaks, and, of course, the pitstop for local fuel and food.

Rasteau has a good, active press office. Other promoted Villages from well before Rasteau are rarely in the footlights – one thinks of BEAUMES-DE-VENISE, VINSOBRES, for example, and one cannot but feel that they are missing a trick.

Rachael Blackmore is an inspiration to many people now, the secret is out, and her tale will encourage others to work harder, to improve, and to take nothing for granted. As it should for any French appellation when it receives promotion. Thanks a million, Rachael, as your trainer Henry de Bromhead was repeating over and over after the great race.

So, to find out how RASTEAU fared in their first 10 years as a CRU, log in, go to Wines and Tastings, click on The First Ten Years of Rasteau in the left hand column, and read a vintage by vintage report on this appellation.

LEARNING ABOUT WINE

JANUARY-MARCH 2021

PEOPLE, PLACES, BOTTLES

Unless you train to be a winemaker, there is no one recognised route into learning about wine. This helps to multiply the cast of characters that can be found around the subject. For me, “self-taught” is inaccurate, since of course, one depends on others – those others being primarily people, places and bottles.

My early tutelage occurred in 1973 when I was taken off the streets of AIX-EN-PROVENCE, my home, where I scratched around backing horses in a PMU bar on LA PLACE DE L’HÔTEL DE VILLE and teaching English in MARSEILLE to the SOCIÉTÉ DES EAUX, the Water Company, and to JACQUES COUSTEAU’s deep sea diving company COMEX.

Example: “you arrive in HOUSTON/ABERDEEN airport – how the heck do you get out of there?” “Err, bonger, je…” etc etc. The art of the French term se débrouiller – to literally unfog yourself – was delivered via my administrations. Little did I know that four years later, I would be in WEST AFRICA during coups d’état trying to do just that myself, but that is another story.

My still grand ami, TIMOTHY JOHNSTON, long time host of JUVENILE’S WINE BAR, rue de RICHELIEU, PARIS, lived in AIX, and at weekends would pour good wine, the lunches extremely extended, TIM noting each wine in a book, often with the label stuck in as well. Hence I received a good few flirtations with les bonnes bouteilles via his hospitality.

Chez my parents, Scotch whisky was drunk with vigour and volume by both Mum and Dad, with the occasional bottle of CHÂTEAU LYNCH BAGES, known as the Englishman’s claret, Irish strictly speaking, at Christmas. Pas grande chose on the learning front there, then.

In March 1973, TIM suggested I came along with him on a visit to the LOIRE; he worked for MELVYN MASTER, an Englishman with a fabulous cellar, his father being a director of the Surrey-based brewery FRIARY MEUX. MELVYN based himself in AIX, the wise man, and exported French wines to the USA.

On this trip, I was exposed to the very, very bonnes bouteilles for the first time. The highlight was a visit to a négociant, BERNARD CHOYER, whose cavernous cellars hollowed out from the local tuffe stood near TOURS.

His maître de chai, a veteran clad in long black leather apron and miner’s lamp, departed on the tram to find some bottles, and emerged with a MONTLOUIS 1959, followed by a VOUVRAY 1947 [older than me, wow!] and a SAINT-ÉMILION CHÂTEAU MICHOTTE [today CORBIN-MICHOTTE] 1929 – pre Second World War.

This is when things got serious. No larking around. Full concentration, but just as much as anything else, a deep, resonant tuning of the senses, as I sipped liquid history in all its serene glory. The MICHOTTE was delicate, aethereal, still in the game, just a little dry on the finish, but what it represented was much more profound than any on the day appraisal.

GÉRARD CHAVE, from whose wisdom I have drunk deeply over now almost 50 years, has always told me: “where is the truth? The truth is in the old bottles – before notoriety came along, with all the coverage and the modern methods.”

As 1973 passed from spring into autumn, my circumstances changed substantially, meaning that by the Longest Day, June 21st, I had set off in my NSU 1200 TT, a white arrow with a rear engine and imminent threat of taking off if you pushed the very bendy accelerator to the ton, 160 km/hr - legal tender in those days along the legendary N7 road that linked PARIS to the MED.

My destination: HERMITAGE, to visit MAX CHAPOUTIER as a hired ghost writer [by MELVYN, a man of incessant ideas] for a new project called the WINES & RESTAURANTS OF THE RHÔNE. There was absolutely nothing written on the RHÔNE then, not a single book, just anecdotes or brief sections in books on the WINES of FRANCE.

More learning came my way in a rush then, the half day spent with MAX CHAPOUTIER encompassing a full vineyard visit to the Mighty Hill, kicking the granite rock and dirt on LES BESSARDS, seeing the rows of often chestnut casks, a legacy of the ARDÈCHE roots of the CHAPOUTIER family, and finally, being seated in a capacious pale brown leather armchair in the boardroom, served a 1961 HERMITAGE BLANC CHANTE-ALOUETTE followed by a 1947 HERMITAGE BLANC CHANTE-ALOUETTE. Another vintage older than me once more tickled my senses, while the title, the Singing Lark, added winsome appeal to these handsome, memorable wines.

By now, people, places and bottles were presenting a full educational onslaught. There was GEORGES VERNAY, attempting to halt the decline of CONDRIEU and its rare VIOGNIER variety – just 12 hectares of CONDRIEU in 1971, which, allied to the 1.7 hectares of CHÂTEAU-GRILLET down the road, was literally all that existed in the whole wide world, apart from the odd plant mixed in a jumble with the SYRAH/SERINE, mostly in the southern sector at CÔTE-RÔTIE.

At CÔTE-RÔTIE there was GEORGES JASMIN, whose father ALEXANDRE had come from CHAMPAGNE to be the chef at the CHÂTEAU d’AMPUIS, GEORGES born in 1904 and passing on wisdom that traversed two World Wars. A gentle request for magnums of the 1971 saw them hand bottled, hand labelled, the capsule waxed by Madame, as was the way in those days.

Or ETIENNE GUIGAL, a reserved man, a warrior for labour, who had worked at J.VIDAL-FLEURY, the owner JOSEPH VIDAL-FLEURY, suited and willowy, very much the SEIGNEUR of AMPUIS, the patron of the business from 1908 until his death in 1976. ETIENNE had hauled himself from basic vineyard tasks to being cellar master, then head vigneron. His keen, promising son was one MARCEL, who in 1984, 38 years after ETIENNE left VIDAL-FLEURY to start his own enterprise, bought LA MAISON VIDAL-FLEURY and made it part of E.GUIGAL.

At CORNAS, there was the incalculable wisdom of AUGUSTE CLAPE, my hero, to draw upon. There was walking in the vineyards discussing soil vineyard care, exposure, fitting together the pieces of Nature’s’ puzzle, before descending into the gloom of the cellar where each plot’s wine was tasted, judged, discussed, with an eye on what each one would bring to the eventual blend.

Meanwhile, the bottles were sending their messages of tuition. That autumn of 1973, I visited CHÂTEAU RAYAS in CHÂTEAUNEUF-DU-PAPE for the first time. LOUIS REYNAUD, a slight man with the air of a kindly professor of letters about him, softly spoken, twinkly eyed, remarked “oui, MONSIEUR LIVINGSTONE, il y a des jolies choses dans la vie” as I drooled over his LIQUOUREUX 1955 BLANC, a golden sheathed wonder.

This was followed by a seminal moment, on my own, in AVIGNON. Up for the cup after RAYAS, I drove there for dinner, and decided to visit the two star MICHELIN restaurant, the height of bourgeois respectability in the city known for its deep-pocketed residents [more stuffy, and an older vibe than AIX, even though AIX was known as the 16th arrondissement of PARIS], HIÉLY LUCULLUS. My clothes were scruffy, my espadrilles worn. I climbed the staircase to the first floor, and asked for a table.

With no prior booking, I was immediately on the back foot, make no mistake about that; coupled with my accented French and my stringy appearance, I was in the doldrums, and was duly shown to a miserable table well away from the coiffeured, CHANEL-clad clientele. “A lovely corner table for you, MONSIEUR,” the lying toad.

“Right,” I thought. Perusing the wine list, well before any notions of grub, I noted a SAINT-ÉMILION CHÂTEAU CANON, vintage 1945. In 1973, there were four vintages of the century – 1929, 1945, 1947 and 1961. Nearly all old bottles to be found in restaurants were BORDEAUX, some were BURGUNDY and SAUTERNES, almost no RHÔNE.

Here was one of the four. Good going. “That will do nicely”, I surmised, so ordered it well before any dishes. It was decanted by a bemused sommelier, the level good.

My orange RHODIA 14 notebook at my side, I settled down to write about my dinner companion. It was fantastically balanced, long and aromatic, a silken delight. I particularly remember noting how many different nuances it delivered as it aired, little nudges and winks along its journey. Two pages of notes were taken.

“Can this wine really have been made while Europe lacked all sorts of vineyard labour, utensils, had no copper for spraying, a shortage of corks, and so on?” I asked myself. It was perfectly wondrous.

By the end of the meal, even the head waiter was visiting my table, and paying attention. Well, I got him into line alright. Then, a bit like the scene in BLOW UP with the YARDBIRDS, when DAVID HEMMINGS wins the fight for the piece of broken guitar, gets out in the street, looks again at it, and tosses it away, I paid the bill, took the empty bottle with me, and drove home to AIX to visit the MISTRAL nightclub. At least there was no fight that night, whereas MARSEILLE GANGSTERS and a VIETNAMIENNE proved my undoing there at a later date.

Such is EDUCATION À L’ANCIENNE, and I wouldn’t have had it any other way.

Wishing all subscribers and readers a very BONNE ANNÉE 2021.